Introduction

In the rural areas of Ethiopia, an exciting citizen participation and feedback process is gaining attention and wielding impressive results. In less than two years, primary health care units (PHCUs), comprised of primary hospitals, health centers and health posts, have more:

- skilled staff, including Medical Officers, Clinical Nurses and Laboratory Technicians

- ambulances – purchased and stationed closer to the communities who need them

District governments are providing timely financial and technical support to local health facilities – not only for training but also for citizen-identified priority actions, including reorganizing pharmacies and improving hygiene and safety. Indeed, citizens and communities are joining the Ministry of Health (MoH) as co-partners to improve the quality and accessibility of health services as never before.

Background

The Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia (FDRE) has increased its commitment to social accountability over the last decade. It has established mechanisms to receive feedback from citizens on the quality of basic public services in various sectors. The largest program of this type is being implemented by the Ministry of Finance and Economic Cooperation (MoFEC) through a World Bank-managed Multi Donor Trust Fund. This program has recently begun Phase 3 and is known as the Ethiopian Social Accountability Program (ESAP).

In support of this government-wide commitment to decentralized and accountable basic service provision, and as part of successful implementation of the Health Sector Transformation Plan (HSTP), the Federal Ministry of Health (FMoH) has developed and is now rolling out a ministry-led, sector-wide citizen feedback process called the Community Scorecard (CSC). This is in addition to Ethiopia’s earlier initiative to have a Maternal, Newborn and Child Health (MNCH) Scorecard for accountability and action: and whose leadership in this area has now been replicated in around 30 other African countries.

Notably, within less than 2 years, the Amhara Regional Health Bureau (ARHB) has done an admirable job to fully implement the CSC process across all of its districts (known as woredas) and communities (or kebeles). The region’s efforts are already benefitting the day-to-day life of individual families, particularly women and young children.

Expected impact

The strategic importance and expected impact of the CSC from the MoH’s and key partners’ perspective includes:

- improving the quality, efficiency, accountability and transparency of primary health care services

- increasing community ownership, engagement and empowerment to improve public health care and take greater responsibility for their own health and wellbeing

- increasing health worker motivation and responsiveness in meeting community needs

- instilling a client-driven, performance-based culture of health service in Ethiopia in which the different levels of government, from local to national, work together in an integrated way with each level performing their inter-related roles in a timely manner

- increasing health-seeking behaviour and client demand for health services

This is done through:

- regular feedback from the community in an unbiased, measurable and actionable way

- regular dialogue and joint monitoring involving health center client representatives, health workers and district offices to respond to community needs

- timely implementation of agreed actions

- management review of health center performance against measurable and comparative indicators developed with input from citizens

CSC implementation status

From top-to-bottom, the FMoH in Ethiopia is placing a high priority on this social accountability initiative. The announcement of its importance was made by the Ministry of Health’s Reform and Good Governance Directorate in the first half of 2017 during consultative meetings with Regional Health Bureaus.

The pilot programme began in Q3 of 2017 in 4 to 5 districts of each of the most populous regions in the country (Oromia, SPNN, Tigray and Amhara regions). As the ‘pilot’ regions, they were encouraged to:

- integrate the CSC social accountability process into their standard operating practices

- contextually adapt the National CSC Guidelines as needed and translate them into regional language

- closely monitor the results of the pilot stage

By the end of 2018, in Amhara Region, the CSC had been rolled-out to all 181 districts and 3,463 communities, with additional progress made in the other 3 regions.

Financial requirements

Financial requirements for implementation of the CSC social accountability process have mostly been met with existing MoH budgetary resources, according to the Head of the Reform and Good Governance Directorate, Ato Assefa Ayde Alaro. Partners have also contributed technical support for start-up activities, training, materials and documentation of the CSC experience so far.

Implementation steps

Step 1: Introduce and verify with the community the CSC performance indicators

Currently, there are 6 indicators:

- Caring, respectful and compassionate service

- Waiting time for service

- Availability of drugs, diagnostic services and supplies

- Infrastructure of facility

- Availability and management of ambulances

- Cleanliness and safety of facility

Step 2: Establish social accountability client councils

Client councils are comprised of 7 community citizens who are:

- identified based on diversity criteria (such as gender, age, religion)

- regarded by the community as natural leaders

- willing to serve on the council for at least one year

The client council members organize and facilitate the community feedback meetings as well as present the communities’ feedback to the health center management and broader community. At this stage in the process, the client councils are trained and orientation/consultative meetings are held with the communities.

Step 3: Conduct quarterly CSC feedback meetings

CSC feedback meetings are conducted every quarter with a representative group of approximately 30 citizens living within a facility’s catchment area. Following discussion of service quality at their local PHCU, individual members vote on their health center’s performance using a color-coded scoring system which facilitates participation by literate and illiterate community members.

Step 4: Present the CSC feedback and scores to the local health center management during a visit to the facility

Visits are done by client council members immediately following the community meeting during which CSC feedback and scores are presented to the local health center management team. At this time, the head of the health centre also updates the client council on actions taken in response to the previous quarter’s citizen feedback.

Step 5: Develop action plans and hold management reviews at all MoH levels

At the Primary Health Care Unit (Health Centre or Primary Hospital) level, an action plan is produced and updated each quarter. The PHCU Head discusses the new round of citizen feedback with the HC Management Team. If some community requests are beyond the authority or capacity of the PHCU to act on, the PHCU Head is required to write a letter to the District Health Office requesting assistance from a higher level within the MoH.

The District Health Office then reviews the CSC color-coded score and action plan for each facility in the district on a quarterly basis, as well as aggregates the scores to determine the district’s overall CSC ranking. The district may also request in writing for support from the Zonal MoH Department if community requests are beyond the capacity of the district. The Zonal Health Department, Regional Health Bureaus and FMoH follow similar management review processes with the zone monitoring quarterly, the region semi-annually and the Federal MoH annually. At the national level, the review is done during a Joint Steering Committee (JSC) meeting which is the highest policy and planning body within the FMoH chaired by the Minister.

Step 6: Hold a district-level interface or town hall consultative meeting

These meetings are organized jointly by the client councils and the District Health Office at least once a year. The interface meetings provide an important opportunity to:

- add additional action points missed from the smaller 30-member rotating community groups

- agree collectively on the level of community contribution (financial, in-kind and labour) in support of citizen-prioritized health service improvements

- receive updates on actions taken by the MoH in response to community requests

- broaden and deepen community ownership to resolve problems with the government and take greater responsibility for one’s own health and well-being since not all problems can be solved by the government alone

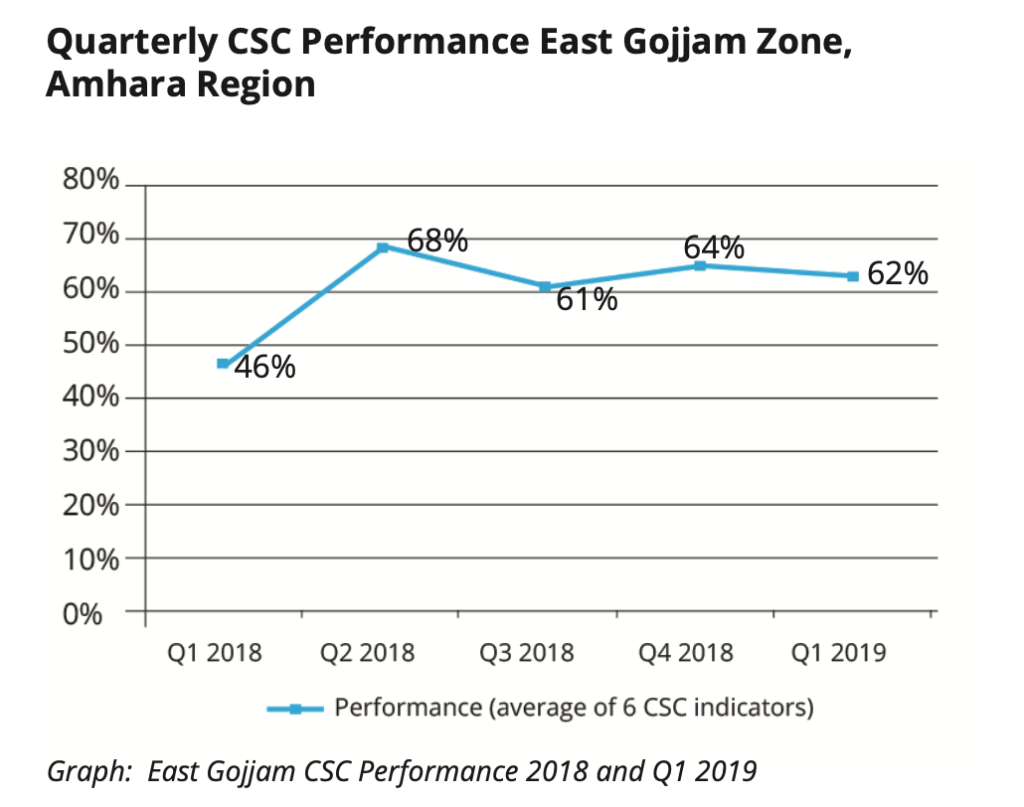

In most cases, after only 2 rounds of quarterly feedback, the envisioned results of the CSC initiative have begun to materialize. This is particularly the case in Amhara Region, where both the piloting and roll-out processes were accelerated and have already reached all districts, communities and 850 PHCUs in the region. Change is also beginning to take place based on community feedback in the pilot districts of the other 3 pilot regions and the FMoH is advocating for accelerated roll-out in those regions. In addition, scale-up in the five remaining rural regions of the country is expected by the end of 2019.

Monitoring

Monitoring, learning and adapting is a programming area where the MoH has stated its commitment. The current monitoring system has some strong foundational elements including:

- putting the client councils and communities in the ‘driver’s seat’ in terms of holding local PHCUs and districts accountable for timely responsiveness to action plans developed based on agreed citizen prioritized concerns

- wanting to build one harmonized, practical set of performance measures for social accountability across the health sector in collaboration with partners

- working on integrating CSC performance reporting into the MoH’s routine HMIS reporting system

We intend to learn and adapt as we move forward with CSC implementation. We also look forward to working with the Ethiopian Social Accountability Program (ESAP) to ensure the health sector indicators and scoring system are the same for use by all communities across the country. We are committed to a measurable, comparable and actionable system.

Ato Assefa Ayde Alaro, Head, Reform and Good Governance Directorate, FMoH

Partner support

Partner support for the CSC initiative in Ethiopia has come most significantly from the Yale Global Health Initiative’s Primary Health Care Transformation Initiative (PTI). This has included support for implementation materials, training and placement of one full-time technical specialist in each of the four pilot regions to support the Regional Health Bureau’s launch the CSC process. In Amhara Region, implementation is also supported by other international partners such as Pathfinder, JSI and ALMA.

We welcome working with partners in Amhara Region and they have already been making significant contributions of technical and financial support, particularly related to training and ongoing mentoring and follow-up.

Dr Abebaw Gebeyehu Worku, Head, Amhara Regional Health Bureau

Achievements to date

A large number of achievements have been documented in Amhara Region, with the below examples worth highlighting from West Gojjam Zone:

- Establishment of maternity waiting rooms in 95% of the health center in the zone and Delivery/MCH Room improvements. This has led to increases in facility-based deliveries by mothers instead of home-based births.

- Purchase and deployment of 54 ambulances paid for by the communities of West Gojjam Zone, with a promise from the Head of the Regional Health Bureau to purchase an equal number of ambulances using Regional Government funds. This will result in 108 new ambulances in the zone which has 104 PHCUs. The ambulances are also being placed at the PHCUs, rather than primarily at the District Office as was done in the past, so that they are closer to patients who need them in an emergency.

- Purchase of 26 generators by health centers using internally generated income from service fees allowed by the MoH. The back-up power source allows these HCs to provide continuous diagnostic services as well as sterilization of medical equipment.

- Hiring of 99 more health workers in 2019 in one district (Yilmana Densa) of West Gojjam Zone with budgetary resources provided by the District Assembly. Out of the 99, 77 have been posted at the PHCU-level (including 30 holding a BS degree and serving in skilled HW positions such as clinical nurses, public health officers, lab technicians and pharmacists) and only 22 posted at the district level.

- Innovative local solutions to drug stock-out challenges with some HCs:

- negotiating with drug distributors for ‘public pharmacy first purchase agreements’ before selling to private pharmacies

- taking a loan from the new MoH Health Insurance Fund administered by the Amhara Regional Health Bureau to buy immediately needed essential medicines that had run out of stock in the HC pharmacy.

Similar results have been reported across the other 14 zones in Amhara Region including these additional types of actions:

- streamlined pharmacy and cashier services to reduce clients’ waiting time

- assignment of HC staff to serve as patient liaison and triage coordinators to ensure those with greatest medical issues are served first and all patients are treated equally without some receiving special privilege in terms of order of service

- infrastructure improvements within PHCU compounds including construction of maternity waiting rooms (with protected latrines and bathing spaces) and establishment of water points

- cleaning and gardening at facilities (including public latrines) so they are safe, hygienic and welcoming

- better management of facility waste disposal to improve hygiene and safety

In addition, health workers emphasize how they are benefitting from the citizen feedback process despite having had reservations in the beginning. Most report feeling empowered and more motivated to perform their duties following institution of the CSC system. There are even reports of service providers seeking clients’ views during out-patient visits and role playing to improve the quality of compassionate and respectful care.

All patients coming to the health center are benefitting from the improvements made due to community feedback, but especially women and children under five years. The health center staff are also benefitting because we better know our strengths and weaknesses. This motivates us in our work.

Sister Bizuayehu Yimenu, CRC Ambassador, Tenta Health Center, East Gojjam Zone

Finally, there are strong indications that the above progress is leading to achievement of one of the overall goals of the program; namely increases in health-seeking behaviour by ordinary citizens and client-demand for health services. An example of this has been at Dembecha Health Center, where facility records indicate that following improvement in the facility’s CSC indicator scores the number of out-patient department visits rose from 65,000 to 295,000 over a 6-monthly period.

In addition to actions being taken jointly by local MoH staff, district/zonal government bodies and community members, in direct response to citizen feedback received through the CSC mechanism, a number of governance and institutional development issues are being positively impacted.

Action plans are being developed and tracked by PHCU staff. District and Zonal MoH offices are monitoring progress and providing technical support. District assemblies are allocating additional funds for specific community requests. Regional Health Bureaus and FMoH are providing incentives and oversight.

These institutionalized management review and response processes across all levels of the MoH are showing promise in helping advance the government’s reform agenda focused on improved responsiveness, management efficiency, financial transparency and equity in service provision.

Community contributions

Another major result of the MoH’s CSC initiative is increased contributions from community members to improve their local health facility. As mentioned above, in one zone alone 54 ambulances have been purchased by communities. Other types of community contributions include the provision of labour, in-kind donations and safety-net funds to ensure health access for the poorest members of a community.

The CSC is accelerating resolution of the communities’ problems and needs.

Abba Mitiku Fentie, Community Council Member and Local Priest, Kudad Kebele

Types of contributions

Source: West Gojjam Zonal Health Office

Labour

- Cleaning and planting greenery in health center compounds

- Helping to construct health posts and toilets/showers for maternity waiting rooms

- Actively providing citizen feedback on quality of health services on a quarterly basis

Supplies

- Food donations so women using Maternity Waiting Rooms receive 3 meals a day

- Local materials (sand, gravel, wood) for construction of health posts and toilets/showers for maternity waiting rooms

Cash

- Women serving in the Health Development Army (HDA) in Kudad Kebele of Yilmana Densa District gave money for transport of donated food items for use by the neediest women delivering at the health center

- Each Kebele in West Gojjam Zone contributed between ETB 200,000 to ETB 2 million (~USD $7,150 to $89,285) for ambulances

Implementation of the CSC brings all community concerns together and addressing those concerns will solve more than 50% of good governance issues in our country.

Sister Dehabo Alamirew, Deputy Head, East Gojjam Zonal Health Department

Best practices

Best practices, predominantly documented from Amhara Regional Health Bureau’s experience due to its admirable success in a short period of time, include:

- Fully institutionalize the CSC tool and process into routine government systems. For example, in Ethiopia the CSC is:

- incorporated into the official Joint Supervisory Visit Checklist used during existing semi-annual MoH support visits to facilities

- a standing agenda item for routine quarterly performance review meetings organized by the Zones with all Districts

- a Key Performance Indicator (KPI) within the health sector’s performance monitoring system for ‘Woreda Transformation’ and ‘High-Performing PHCU’ designation.

- Ensure the performance indicators in the CSC tool remain measurable and comparable and are aggregated so each level of the health sector obtains a quarterly score.

- Keep costs low and utilize domestic resources to the extent possible. For example, combine CSC training times with other routine health worker meetings, reduce the length of trainings, and use self-learning training videos as an alternative to face-to-face trainings.

- Encourage regional tailoring of the national guidelines to build ownership, take into account regional context and capacity, and translate into local language.

- Ensure the CSC process is genuinely ‘citizen/ community-led’ and that citizens providing feedback represent the diversity of the community. In Amhara Region, this has translated into no staff, or volunteer cadres of MoH health workers, being present during the community feedback meetings and scoring.

- Ensure citizens providing feedback represent the diversity of the community and rotate on a regular basis.

- Hold community feedback and scoring meetings consistently on a quarterly basis to keep momentum going. Don’t skip a quarterly meeting but also don’t hold too many meetings. Quarterly meetings provide sufficient time for action to reasonably be taken at the local level on most issues; or be elevated for action to a higher MoH level as needed.

- Update the Action Plans at the health center within no more than a week after each round of citizen feedback and quickly implement as many agreed actions as possible. According to zonal officers interviewed, for approximately 80% of the issues raised by the community, the health center have been found to have the capacity and authority to implement the required actions without help from higher MoH levels.

- Ensure Management Review Meetings take place each round, not only at the health center but also quarterly at the district level and at least semi-annually at the Zonal level. Management reviews need to result in written and disseminated feedback on performance and a response to any requests made for higher MoH action.

- Recognize ’Leadership Matters’. Executive management reviews need to take place at least annually at the regional and national levels. During start-up, a well-communicated directive and visible endorsement by the Minister and Regional Health Bureau Head added significantly to how quickly and comprehensively the CSC process was implemented in Amhara Region.

- Offer ‘no or nominal-cost’ incentives to motivate health workers and promote community material and/or financial contributions. These include health worker recognition during routine staff meetings, certificates, posted photos of ‘Employee of the Quarter’, and the selection of one health worker by his/her peers to serve on a rotating basis as the CRC (Caring, Respectful and Compassionate service) Ambassador. Innovatively, the Head of the Amhara Regional Health Bureau also made a ‘matching funds’ promise to communities. This meant that that for each ambulance purchased through community contributions, the Region would finance an additional new ambulance for their area. In one zone alone, communities raised enough money to buy 54 ambulances and now await the other 54 ambulances to be financed by the regional government.

- Remember the Community Scorecard (CSC) initiative is much more than a measurable health facility performance tool. It is a community-led process that includes open discussion, individual scoring, face-to-face feedback and action plan tracking with local health workers, and monitoring and support from all levels of the health system.

Communities are very eager and engaged. If the quarterly feedback meetings are delayed, the community demands the meetings be held.

Ato Gebeyaw Temesgen, Tenta Health Center, Head

Lessons learned

Lesson 1

The piloting affirmed feasibility and effectiveness of the CSC process, as well as the importance of seeking community input on the process itself. For example, communities suggested a change in one of the 6 MoH proposed CSC indicators – to remove a Management Performance indictor (which they did not feel they had the expertise to rate) while adding a ‘Clean and Safe Health’ (CASH) facilities indicator which they indicated significantly impacted both the demand and quality of service at health centers. Feedback from communities also suggests that some of the indicators be separated to score quality of specific services more accurately (such as separately scoring drug availability, laboratory services and card room services)

Therefore, the final 6 CSC indicators have been revised in the national guidelines and standardized for MoH analysis and comparison purposes. Documentation from the Pilot Phase in the 4 regions will be shared with the 5 other rural regions and each of those regions will be encouraged to undertake their own test phase before scaling-up. The FMoH will also review the CSC health sector indicators recently proposed by ESAP 3 and work jointly with key stakeholders to ensure one standardized set of indicators and performance measurements for the CSC exists and that they are based on field experience and feedback from the communities

Partnership is essential when implementing new initiatives like the CSC because it maximizes the use of resources and builds synergy. Non-governmental partners need to work extremely closely with government at all levels so as to avoid resource duplication and not create parallel systems.

Dr Abebaw Gebeyehu Worku, Head, Amhara Regional Health Bureau

Lesson 2

Partners with relevant technical skills and other resources add value and help expedite learning and scale-up. Therefore, the FMoH, Regions and Zones will be encouraged to engage partners earlier, strengthen and expand existing partnerships, and invite partners to Zonal/District review meetings.

Lesson 3

Tangible actions in response to community requests can take place within a 3-month period by the health center, the district or the community themselves with little need for outside resources. Therefore, citizens are to be trusted to put forward requests and feedback that is nearly always reasonable, actionable and often within the scope of local health workers’ current authorities and mandate. Timely, tangible action also has made it easier to continue finding 30 new community members each round to rotate in and rank their facility at the next quarterly feedback meeting.

Lesson 4

New staff CSC training, as well as Refresher training, is acknowledged by the FMoH as important and the costliest component of the CSC process. Therefore, to reduce the cost of future training, a self-learning Training Video is being developed and will be tested as an alternate to face-to-face training. In addition, discussions with a wider group of partner organizations – particularly Ethiopian CSOs actively engaged as social accountability trainers in the Ministry of Finance and Economic Cooperation’s (MoFEC’s) Ethiopian Social Accountability Programme Phase 3 (ESAP 3) – will take place to leverage and coordinate existing training resources for the health sector.

Lesson 5

Though some effort had been made to hold Consultative/Orientation Meetings with the broader community through a town hall format before implementation began, in most cases orientation was only provided to the 7-member Client Councils. Therefore, more attention needs to be paid to this step at the start in new districts. This will reduce potential misunderstandings of the CSC and make it easier to find a rotating group of 30 community members to provide quarterly feedback and obtain full endorsement on the 7-member Client Council composition, especially during the first 2 quarters when some hesitancy has been noted.

Lesson 6

Though some concerns existed initially that the Client Council would need to be literate to perform their functions with full knowledge, skill and realistic expectations, most key informants did not consider this a problem. Therefore, this will not likely be prioritized as, in reality, nearly all 7-member Client Councils have at least one or more literate members. Rather community expectations can be better managed by providing adequate background information during Client Council training on the type of services that can realistically be expected at primary health care units.

Lesson 7

Out of the 6 CSC indicators, resolving issues related to the availability of medicines and other essential supplies/equipment has proven the hardest for the PHCUs and communities to do on their own – despite some laudable and innovative efforts made by a few. Therefore, more attention is being given at higher levels within the health sector to address this common community concern.

Lesson 8

MoFEC’s Ethiopia Social Accountability Programme Phase 3 (ESAP 3) recently began and will build on lessons learned from its earlier work as well as lessons from the MoH’s CSC initiative. Therefore, to ensure harmonization and avoid duplication of effort in the health sector related to improvement of PHCU service quality and District Health Office transformation, it has been agreed that a high-level National Task Force will be established to synchronize these two major citizen feedback programmes and involve all key stakeholders in the country working on social accountability.

Next steps

The MoH is keen to continue to scale-up the CSC experience in all other rural regions of the country. Current plans, to be coordinated by the Reform and Good Governance Directorate within the FMoH with the addition of a full-time coordinator, include:

- accelerate implementation in the 3 other most populous regions (Oromia, Tigray and SPPN) with another 600 communities reached by the end of 2019

- initiate pilot activities in the remaining 5 rural regions of the country (Afar, Gambella, Benishangul-Gumuz, Harari, Somali)

- modify the implementation approach for pastoralist areas

- ensure MoH integration across all levels continues and action remains timely

- share experiences and learnings between the MoH and ESAP 3, and work towards alignment and complementarity of the CSC tool and implementation approaches in the health sector.

- continue to learn, document, generate knowledge and advocate for sustainable citizen feedback and social accountability processes in the health sector

Potential opportunities to strengthen CSC impact in Ethiopia and beyond

Recommendations related to ongoing strengthening, scale-up and sustainability of the CSC work in Ethiopia include:

- Ensure community members providing feedback continue to represent diversity of the community, especially PHCU users. This translates into always ensuring appropriate gender, age, religion and socio-economic balance.

- Post the latest color-coded CSC scores and Quarterly CSC Action Plan in a visible location at the PCHUs. Do the same at the District Health Office.

- Include health center Heads and/or CRC Ambassadors from high-performing PCHUs to be a part of the Zones scale-up efforts so that peers learn from one another and service as a peer trainer provides incentive for these high performing health workers.

- Identify low/no-cost ways to ensure that at least annual community-wide Interface Meetings take place.

- Continue to reflect on how best to add value sustainably from partner support and ensure all stakeholders use common standards of performance for social accountability in the health sector. Partner engagement and resource provision need not reduce the level of hands-on technical support, budgetary support and bottleneck resolution by MoH officers at the PHCU, district, zonal and regional levels. Assign at least one focal person at the zonal level to coordinate the CSC process within the zone.

- Improve the digital submission, storage and federal-level access to CSC dashboards and action plans. Ensure these are integrated into the newly established DHIS2 system in the country as part of the routinely monitored cache of governance and management dashboards. Work with key stakeholders to develop a digital Action Tracker.

- More systematically engage other relevant parts of the MoH, particularly the Health Extension and Primary Health Care Directorate and the Pharmaceuticals and Medical Equipment Directorate, in the CSC management review processes at all levels to optimize impact of this citizen-led initiative. CSC indicators (such as Caring, Respectful and Compassionate service delivery and availability of essential drugs, equipment, diagnostic services) fundamentally relate to how effectively all national health programmes are executed. In addition, community feedback on ambulance service and drugs/equipment is relevant for the MoH Supplies Departments; and patient waiting time may be of interest to the MoH HR Departments. Quarterly Performance Review Meetings and Action Plan development at the zonal level need to include not only Quality Performance/M&E Officers but also those responsible for the provision of MCH/medical services at the district level (Hospital CEOs, MCH Officers and Curative Rehabilitative Change Process (CRCP) Officers).

- Analyse existing scoring data and action plans in more depth to determine if adjustments may be warranted over time to achieve the greatest impact. For example:

- Are there correlations between the:

- distance of a community (Kebele) to the health center and CSC scores/regularity of feedback meetings?

- distance of a community to the health center and level of community engagement and contribution?

- length of MoH service of the Health Facility Head and the facility’s CSC scores?

- Does equal weighting, aggregating and averaging of the scores for the 6 CSC indicators lead to masking the performance of some indicators even though the overall color-coded rank remains the same or improves?

- Might a somewhat simpler 3-color scoring system work as well as the current 5-color system while achieving the same results?

- Does the Theory of Change in Amhara Region (which emphasizes the importance of no MoH cadre involvement in community feedback meetings and rotation of citizen group members) make a substantial difference in comparison to approaches being taken in the other 3 populous regions (with Oromia and SPNN Regions using volunteer female CHWs, known as the Health Development Army (HDA), to represent the community and Tigray Region using existing health center Board community members)? Undertake a deeper analysis of new costs related to CSC implementation (both start-up and recurrent) to ensure sustainability and scale-up of the impressive work done so far.

- Are there correlations between the:

- Advocate jointly across MoH levels for additional funding for the CSC program, when needed, from both domestic resources as well as from partners. This is important since fulfilment of the designated roles and responsibilities across the various levels of government is critical for this social accountability initiative to be successful over the long-term.

- Maintain social accountability through the CSC as a high-profile priority for top political and technical leadership at the federal and regional levels so the positive momentum is maintained.

Conclusion

The future looks bright for continued implementation of the CSC tool and citizen feedback process in Ethiopia with top political and technical leaders, health workers, community members and partners strongly affirming their support and continued engagement in full institutionalization and implementation of this health sector social accountability process.

Opportunities exist for other countries too – when appropriately contextualized and supported by their leadership – for similar community-owned feedback and accountability mechanisms to be established.

The CSC is an important tool that contributes to good governance at the health facility level and ensures that the community gets what they need.

Honourable Minister Seharela Abdulahi, State Minister of Federal Ministry of Health, Ethiopia

The CSC makes the community feel as the owner of the health centers and health services. Social accountability will come. Government responsiveness is different when the community regularly and measurably is engaged.

Dr Abebaw Gebeyehu Worku, Head, Amhara Regional Health Bureau

This is a great process and needs to continue.

Wzt Zingorsh Ayalehew, Health Extension Worker, Dembecha Woreda, West Gojjam Zone

Communities are very eager and engaged. If the quarterly feedback meetings are delayed, the community demands the meetings be held.

Ato Gebeyaw Temesgen, Tenta Health Center, Head