A tool to support achievement of country RMNCAH goals

Uganda has made commendable progress in improving reproductive, maternal, newborn, child and adolescent health (RMNCAH) indices over the recent past. Between 1995 and 2016, child mortality decreased from 156 to 64 per 1000 live births with the annual rate of reduction increasing from 1.2% to 8.1% between 2006 and 2011. Maternal mortality reduced by 33% over the last 20 years. Despite this progress, preventable deaths in mothers and children remain high with considerable disparities across the country. Uganda has prioritized improvement of RMNCAH through the country’s RMNCAH Sharpened Plan (2016-2020). The overall goal of the Sharpened Plan is to end preventable maternal, newborn, child and adolescent deaths and improve the health and quality of life of women, adolescents and children in Uganda. The RMNCAH scorecard tool for accountability and action has been identified as necessary to support the achievement of this goal.

RMNCAH scorecard management tools

ALMA has supported 29 African countries to develop and implement RMNCAH country scorecard management tools to support tracking progress towards national targets, strengthen accountability and drive action. The scorecard tools monitor performance of prioritized indicators across the RMNCAH continuum of care, at national and sub-national level. They are country-owned, reflecting each country’s priorities, and integrated into existing country mechanisms. Since 2015, ALMA has been working with Uganda’s Ministry of Health (MOH) to support the use of the RMNCAH scorecard tool in Uganda.

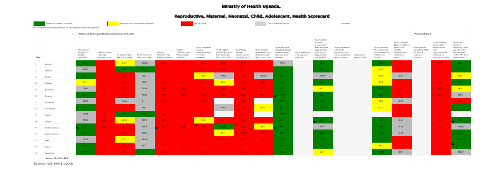

Uganda’s scorecard tool is populated using routine data from the country’s health management information system (HMIS) and is hosted within the District Health Information System (DHIS2) platform. The scorecard tool consists of a display of indicator performance using traffic-light colours. The scorecard is reviewed during management meetings during which performance is reviewed and bottleneck analysis is conducted to generate actions to improve underperforming indicators.

Development and implementation of Uganda’s RMNCAH scorecard tool

The scorecard development was led by the ministry of health. The process, which involved defining the purpose of the tool and agreeing on priority indicators and implementation modalities, included stakeholder consultations which brought together officials from the national level ministry of health (Child health, Reproductive health, Department of Planning, and Division of Health Information and Senior Management), the district level (District Health Officers, RMNCAH focal points (usually the Assistant District Health Officer and district biostatisticians) and partner organizations including: UNICEF, the World Health Organization (WHO), United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), USAID, ALMA and Uganda National Health Consumers Organization (UNAHCO). The first RMNCAH scorecard was published in Q2 2016. The overall purpose of Uganda’s RMNCAH scorecard tool is to support evidence-based management decision-making, enhance transparency and strengthen accountability for results based on the Sharpened Plan.

Under Uganda’s decentralized governance system, the district level is semi-autonomous with political, administrative and fiscal authority. The District Local Government, which includes the District Health Management Team (DHMT), is responsible for delivery of health services, planning, management and implementation of policies. As such, a district-led approach was chosen for the use of the scorecard tool.

Implementation of the scorecard tool is rooted at the district level and follows a quarterly accountability cycle which consist of:

- review of indicator performance

- action generation in response to performance

- action implementation and follow-up

In general, district biostatisticians are responsible for ensuring availability of the scorecard for review, while Assistant District Health Officers (ADHOs), who also oversee district RMNCAH programmes, are responsible for the review of the scorecards and action follow up. A recent assessment of the scorecard process found that in all districts assessed, the scorecard is reviewed during district quarterly review meetings, which are an integral part of the district health management system. During scorecard discussions, poorly performing indicators and health facilities are highlighted, reasons for inadequate performance identified, and corrective actions agreed upon. In addition to the review of the scorecard at programme level, several districts share their scorecards with other key district stakeholders including communities and district leaders.

Partners including UNICEF, UNFPA, USAID, The World Bank, WHO and others play an important role in enabling implementation of the scorecard. Partner support has included funding of scorecard trainings, review meetings and other forums where the scorecard is disseminated, such as regional RMNCAH assemblies. District-based partners including RHITES (USAID), Clinton Health Access Initiative (CHAI), Community and District Empowerment for Scale-up (CODES), Uganda Health Marketing Group also participate in the review process and support implementation of corrective actions.

The MOH national level maintains the responsibility of ensuring that quality-assured data are available on DHIS2 as per MOH guidelines, the scorecard is updated and available every quarter. The Maternal and Child Health (MCH) division is responsible for coordinating the implementation of the scorecard tool including ensuring continuous district trainings (new and refresher), mobilizing support for enablers of use at district level and to some extent supporting bottleneck resolution. The MCH division also identifies opportunities for wide sharing of the scorecard such as at national RMNCAH assemblies.

Successes in the use of the scorecard

The use of the scorecard tool has contributed to better RMNCAH programme oversight and performance at the district level, particularly in the following areas:

- strengthened evidence-based performance monitoring,

- widened stakeholder engagement and increased transparency

- strengthened action generation and implementation

These successes together have markedly increased accountability for RMNCAH, using a bottom-up approach.

Strengthened evidence-based performance monitoring

Review of health programme performance is a core function of the DHMT and wider district leadership. All districts conduct quarterly review meetings led by the DHO and generally attended by DHMT members, focal persons of health programmes, district leaders (such as Chief Administrative Officer (CAO), Assistant CAO, District Planner, District Secretary for Health), Health Sub-District In-charges, high volume Health Facility In-charges, Implementing Partners, representatives from private practitioners, and head of health associations. Integration of the scorecard into these meetings has provided a structured mechanism for comprehensive review of RMNCAH programme performance. The ability to show performance of multiple levels (district, health sub-district and health facility) and indicators across the continuum of care as a snapshot, and ease of interpretation has been cited by numerous users as a key advantage of the scorecard. The scorecard has greatly enabled use of existing data and robust evidence-based discussions about shortfalls and successes in performance.

Before introduction of the scorecard, we had people looking at data from facility registers to assess performance, this did not reflect true performance. The scorecard shows actual performance for all levels.

Jinja District ADHO

Widened stakeholder engagement and increased transparency

High-level engagement and advocacy

In addition to its use in quarterly programmatic reviews, the scorecard is shared with district leaders in several districts. This has enabled leaders to be more aware and engaged in the RMNCAH programme and provided an avenue for advocacy for resources. In 2018, the MCH division-MOH added to scorecard trainings, a one day session for district leaders, recognizing the importance of engagement of leaders in bottleneck resolution. This training primarily targets District Chief Administrative Officers (CAO) who are the district chief accounting officers. CAOs are now involved in the scorecard accountability process and have played an important role in addressing bottlenecks to performance. Areas of district leadership support include, among others, improvement of health facility infrastructure, hiring more health workers and direct funding to RMNCAH programmes. Political leaders also contribute to optimizing the use of the scorecard. For Example, in Mukono District a copy of the scorecard is sent to the District Local Council 5 (LC5) Chairperson every quarter. The LC5 Chairperson leads the LC5 council which is the highest elected local government governance structure at district level. Among other responsibilities, the LC5 council enacts local laws, ensures effective budgeting and planning for public services and plays a role in oversight of delivery of services. In Mukono an LC5 councillor who is also Secretary for Health leads community discussions of the scorecard while in Mubende, the LC5 chairman uses the scorecard to engage with health facilities to discuss progress and challenges in RMNCAH.

The scorecard is popular with political leaders. During one review meeting we used graphs to describe performance and they complained: “we do not understand your graphs, use the scorecard.

Mukono Biostatistician

Community engagement

Because of its simplicity, the scorecard has been effectively used to identify challenges in uptake of services and agree on joint problem-solving with communities. Across districts, scorecard focal points noted that using colour codes rather than percentages greatly simplifies discussion on performance with communities. As such, in Mukono, scorecard reviews have been integrated into routine sub-county dialogues (barazas), a social accountability mechanism where the local government interacts with communities to discuss public service delivery. Scorecard discussions are led by the District Secretary of Health and communities provide insights into reasons for performance. Scorecard discussions with communities have led to identification of causes of, and solutions for, low performance of immunization, antenatal care (ANC) and postnatal care (PNC), among others. Interventions that have resulted include targeted health messages to address community misconceptions, improvement of health facility conditions and adjustments to community level services to address identified needs.

The scorecard has improved the relationship between service providers and service users. During community dialogues we get to know how the users perceive services. We then empower health workers and let the communities lead monitoring of services. This has promoted common understanding of challenges and solutions.

Mukono Biostatistician

Strengthened action generation and implementation

One of the core functions of the scorecard is to motivate corrective actions in response to poor performance and monitor follow-up performance. This function has been successfully realized across all districts using the scorecard. As part of the district-led model individual districts focus on a subset of the national indicators based on their own prioritization, updating and adjusting the number of indicators monitored as needed. The ADHO is responsible for tracking actions to ensure their implementation and updating follow-up meetings. Actions are targeted to multiple levels including district, health-facility, community and district political as described above.

Service delivery

In response to poor performance of the indicator “fully immunised by one-year”, Jinja DHMT supported health facilities to implement a system to track appointments and trace defaulters in communities. This system led to increased health facility appointments but also supports linkage to outreach immunizations, for those unable to go to health facilities. The percentage of fully immunized children increased from 73% in Q1 2020 to 85% in Q3 2020.

Following poor performance in a number of indicators including coverage of PNC and Prevention of Maternal to Child Transmission of HIV, the health facility in-charge of one of the highest volume health centers in the district, assigned responsibility of indicator performance to specific staff. This included responsibility for continuously assessing bottlenecks and ensuring corrective actions were implemented. This system also includes incentivising staff whose indicators show improved performance. Such actions have been associated with improved service delivery at health facility level and steady bottom-up improvements across the district.

Resource mobilization

In response to poor performance in family planning in Mukono, the DHMT advocated for more financing from the district political leadership. This led to the allocation of UGX 8Million ($2200) every quarter from the district budget to support the family planning programme.

Discussions on low performance of maternal health indicators in Mukono identified poor conditions in health facilities as a contributory factor. The District CAO, using a discretionary development grant, authorized the repair of maternal wards and construction of waiting shelters. Additional interventions included repeated discussions on performance with communities during community dialogues. A steady increase in performance in multiple indictors has been noted over the period Q4 2018 to Q2 2020 including: health facility deliveries from 59% to 64%, PNC after 6 days from 10% to 21% and ANC4 from 30% to 35%.

In Bukomansimbi only 18% of pregnant women reportedly attended their first ANC visit within the first trimester. Multiple causes were identified which led to several actions including lobbying the district leadership to increase the number of midwives at health centers (HC II) which collectively serve a large population of the district. Midwives were hired for all health center IIs. One year later, performance had increased to 32%.

The coverage of institutional deliveries was only 33% and caesarean section deliveries only 0.2% of all deliveries in Bukomansimbi in Q3 2018. One of the major causes being shortage of capacity (human and equipment) and few public health facilities. In response, the DHMT worked with a large private sector health provider and research partner to build capacity in both public and private health facilities including posting a medical doctor to conduct caesarean sections in one of the busiest facilities and equipping other facilities. Within one year, institutional deliveries had increased to 40% and caesarean section rate to 4.5%.

UNICEF contributed $10000 to Mukono district to support its annual work plan following the districts robust development of the plan using evidence from the scorecard to inform prioritization of areas of focus and intervention choices.

Community mobilization

In response to low ANC coverage, an innovative “group antenatal system” was supported in Jinja district. Health facilities group mothers with ANC appointments on the same day, living in the same area. The women are then encouraged to remind and motivate each other to attend appointments. Community health education on the importance of ANC was also intensified. These interventions were associated with an increase in ANC4 from 56% to 82% within two quarters.

In Mukono community discussions around low coverage of early ANC identified reasons for starting ANC late as: the common community practice of using the beginning of “the baby’s kicks” as the cue to start ANC, the cultural belief that attending “too many” ANC visits was dangerous for the baby and overall poor understanding of benefits of ANC. These findings led to community health education tailored to address these misconceptions. Early attendance of ANC1 subsequently increased from 17.5% to 27% within a year.

In Mukono, discussions on low uptake of IPTp3 revealed misconceptions about side-effects and low importance of more than one dose of IPTp. Subsequently, health education talks in the community and in antenatal clinics were designed to address these misconceptions and this was associated with over 20% increase in performance over three quarters.

Similar discussions with communities in Kasawo about high immunization drop-out rates revealed lack of transportation as a major challenge. Health facilities also lack ability to consistently conduct immunizations in the community. The community and health facility leaders agreed to work together to find a solution to this barrier including provision of free transport to the most vulnerable families.

In Masaka, community leaders agreed to institute community regulation to penalize men who do not support their wives to attend antenatal and postnatal care in order to increase uptake of these services and avoid maternal deaths

In Masaka, poor performance in early ANC and PNC led to the District Health Educator intensifying messaging on the importance of these areas. An increase in early ANC from 31% to 44% within two quarters was observed. The district further engaged the Clinton Health Initiative, and implementing partner, to support implementation of community mobilization to increase uptake of full immunization services for children and a similar upward trend in performance from 73% to 85% was reported.

Summary

The Uganda MOH has successfully steered the development and decentralization of country’s RMNCAH scorecard tool to the district level. The district-led approach has been effective in firmly integrating the scorecard tool into district review and accountability mechanisms. The scorecard is a standing agenda item in district quarterly review meetings led by District Health Management Teams. As a result of ease in interpretation and concise visual presentation, the scorecard is well liked and effectively used by district leaders. This has led to increased involvement and support of leaders and mobilization of district local government resources. The scorecard has also been used to better engage and serve communities. Findings from the scorecard contribute to focusing community health systems and the scorecard is also directly discussed with communities for joint problem-solving for underperforming indicators.

Development and implementing partners, at both national and district level, have played a critical role in enabling the implementation of the scorecard. This has been through funding of the scale-up of the scorecard process, building district capacity to optimally utilize the tool, funding review meetings and supporting action implementation. While there are opportunities for strengthening the use of the scorecard further, the Uganda experience demonstrates the potential of the tool to galvanize stakeholders and support progress towards better health and wellbeing for women children and adolescents.