When I first encountered the community scorecard, I did not realise I was stepping into a process that would redefine how communities engage with the services meant to uplift them. I remember the first community dialogue session in Vuvulane, Eswatini. People sat with their arms crossed, uncertain. Someone even asked outright: “Will anything actually change from this, or are we just filling out another form?”

That question stuck with me. And honestly, I understood it. How many times had community members been asked for their opinions, only to see nothing happen?

But what I witnessed over the following months working with the Eswatini Malaria Youth Corps in areas like Vuvulane and Sithobela changed how I think about accountability, participation, and what it really means to put communities at the centre of health services.

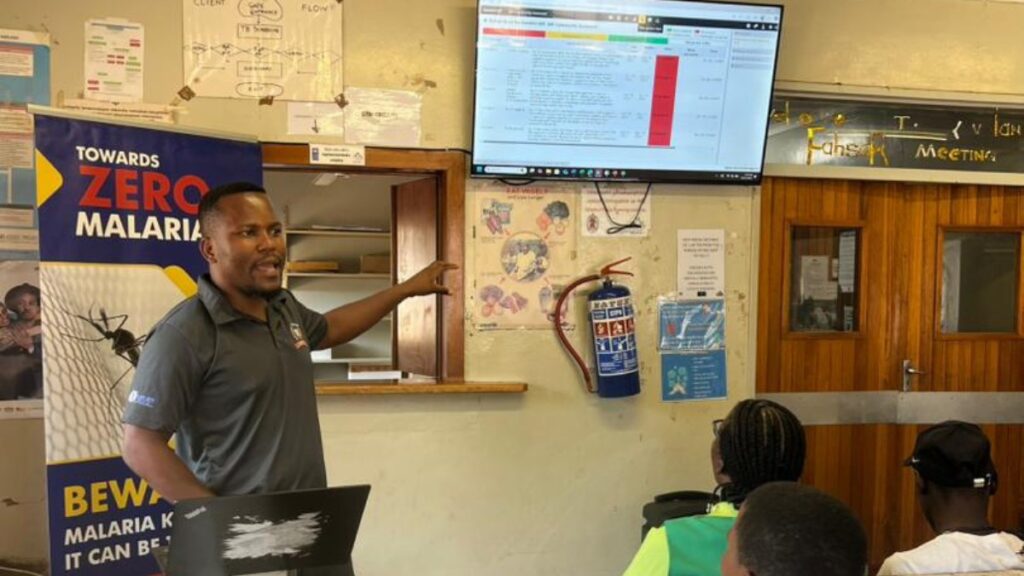

Bheki Bhembe introducing the scorecard tool to youth champions in Eswatini.

What is a community scorecard?

Before I get into the story, let me explain. A community scorecard brings together community members and service providers to have structured conversations about health services. People score different aspects of care, such as access to clinics, how staff communicate with patients, availability of medicines, youth-friendly services.

But the scores matter less than what follows. Why did you give that score? What specific problems are you facing? What would make things better?

Service providers respond – not defensively, but honestly. They explain constraints, clarify misunderstandings, and together with the community, create an action plan. The scorecard gives structure to conversations that often don’t happen at all.

When people start talking

That first session in Vuvulane was tense at the beginning. But once people started sharing their experiences, the atmosphere shifted. Women talked about long waits at clinics when they had children at home. Young people mentioned feeling judged when seeking reproductive health services. Community members pointed out that information about malaria prevention wasn’t reaching everyone, especially in rural pockets.

I watched clinic staff listen – really listen. And then something happened that I didn’t expect. One nurse explained that staff shortages meant she was often the only person handling a full waiting room. A community health worker shared that he had to cover three villages on foot and sometimes couldn’t reach everyone who needed bed nets.

Suddenly, the conversation shifted from blame to reality as both sides understood each other’s constraints. And from that understanding, we built an action plan together – one that was actually achievable.

Gender dynamics in health and the Gender Equality Fund Project

In Sithobela, where we implemented community scorecards as part of the Gender Equality Fund (GEF) project supported by the Global Fund, the discussions went deeper. We examined how gender dynamics shaped who could access health services and who made decisions about seeking care.

Women talked about needing permission from male relatives to visit clinics. Young women mentioned feeling uncomfortable discussing health issues in front of older community members. Traditional gender roles meant they cared for sick family members but had little say in treatment decisions.

The scorecard process gave us a way to document these barriers and translate them into action points. It showed us that equity requires deliberate attention to who is included in conversations and whose voices are heard in decision-making.

From monitoring tool to advocacy instrument

Here is something I didn’t fully appreciate at first: while some people may see the scorecard as a way to monitor services, in essence it is a powerful advocacy tool.

When communities identify specific gaps – whether it is staff shortages, lack of youth-friendly spaces, communication breakdowns – they generate concrete, community-rooted evidence that can be taken to policymakers and district health officials.

During the youth corps’ work this past quarter (April to June 2025), we saw this in action. In multi-stakeholder workshops with the Ministry of Health, the national malaria programme, End Malaria Fund, and ALMA representatives, scorecard findings gave youth and communities a seat at the table. We presented data that came directly from the people affected by these services.

That shift – from complaint to evidence-based conversation – makes it harder to dismiss community concerns as anecdotal.

The work continues

The Eswatini Malaria Youth Corps has been rolling out community scorecards across Eswatini’s four regions, with particular focus on Hhohho and Lubombo where malaria cases remain highest. We have trained 117 youth leaders – 48 women and girls at Vuvulane, 69 women and girls at Sthobela – on how to facilitate these dialogues. We have held sessions in rural communities, partnered with local clinics, and worked alongside chiefs and community leaders.

A specific challenge that emerged was around bed net distribution timing. Community health workers typically distribute bed nets during working hours, but most Vuvulane community members work in the fields and only return after lunch. This scheduling conflict meant families were often unavailable when health workers came by, creating a barrier to accessing this critical malaria prevention tool. The scorecard process helped identify this practical issue and opened discussions about adjusting distribution schedules to better align with community availability.

When the process works, it really works. I have seen communities that were passive recipients of health services become active participants in shaping those services. I have watched young people who thought they had no voice in health decisions step up as facilitators and advocates.

Why this matters beyond malaria

While our focus with the youth corps is on malaria elimination, the scorecard approach applies to any service delivery challenge. It is about creating spaces where communities and service providers can have honest, structured conversations – accountability that is constructive, not punitive.

Most importantly, it recognises that people closest to the problem often have the clearest insights into solutions.

Looking back at that first session in Vuvulane, I realise now why it stuck with me. That man who asked if anything would actually change? He came to the follow-up session two months later. He had seen improvements: better communication and friendlier-responsive staff. Not everything was fixed. But something had changed. His voice mattered.

That is what the scorecard makes possible. Not perfection, but participation. Not instant transformation, but measurable progress. And the understanding that health services work best when communities and providers are partners, not adversaries.

About the author

Bheki Bhembe is an Environmental Health Practitioner with over five years of experience in community development. He volunteers with the Eswatini Malaria Youth Corps (EMYC), focusing on youth empowerment, gender equality, and evidence-based advocacy through community engagement tools like the scorecard approach.